Occupying a combined space of 10.9 Million sq. ft., the Highland Park Plant, Packard Plant, and Russel Industrial Center are Detroit’s largest abandoned automotive heritage sites. Once thriving with activity, these monoliths of automotive production fell silent long ago and have haunted the city’s landscape for decades. However, in the midst of Detroit’s comeback, these mammoth’s of Detroit’s past are undergoing a renaissance of their own, providing a portal to what was and what could be in a city that has finally started down the road to recovery.

Highland Park Plant

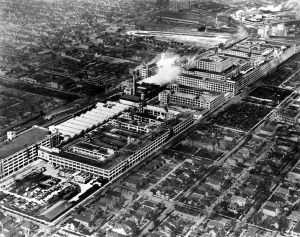

Ford’s Highland Park Ford Plant was the first automotive production facility in the world to implement a moving assembly line. Designed by Albert Kahn, it was opened in 1910 and was the second production facility for the Model T. The complex included offices, factories, a power plant and a foundry. Its design incorporated an open floor plan that allowed for efficient arrangement of machinery, an abundance of windows to provide natural light, and additional space for expansion should production demands increase.

It was the efficiency of Highland Park’s assembly line that cemented Henry Ford’s legacy in automotive History. Ford, who was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1967, used the Highland Park plant to refine his mass production methods after moving Model T assembly out of the Piquette Plant. He did so with the assistance of fellow Hall of Fame Inductee Clarence Avery (Inducted in 1990), who focused on developing the moving assembly line while working with a stopwatch to speed up production. The implementation of the assembly line in 1913 reduced the assembly time of a Model T from 728 minutes to 93 minutes, enabling Ford to continually lower the price of the T while also paying his workers higher wages. Ford appointed William Knudsen, also a Hall of Fame Inductee (1968), as production manager of the Highland Park Plant in 1912.

In the late 1920’s, production demands caused Ford to move automobile assembly to the new River Rouge Plant in nearby Dearborn. Though Highland Park was used for military production during WWII, it became largely dormant following the production shift. In 1978, it was designated a National Historic Landmark. In 2013, an organization called the Woodward Avenue Action Association led by Executive Director Deborah Schutt reached a purchase agreement to establish an automotive welcome center and visitor attraction at the Highland Park Plant’s admin building. Renovations are scheduled to start this year, and the association intends to revitalize as much of the legendary factory as it can afford.

Packard Plant

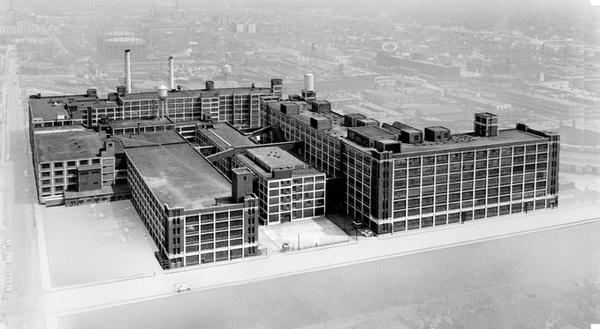

The Packard Plant is Detroit’s largest white elephant. Once the home Packard Motor Car Co., the long forlorn complex was designed by Albert Kahn and completed in 1911. The reinforced concrete structure was the first automobile factory of its kind, and would serve as a template for future factories all over the world. Occupying 3,500,000 sq. ft., the plant was a world class production facility that helped Packard become one of the world’s foremost luxury brands, outselling marques like Cadillac and Lincoln during the 1920’s.

Many potential buyers for the property came and went, but in December of 2013 it was Spanish investor Fernando Palazuelo who purchased the plant for just for $405,000 after bids from two other buyers fell through. He intends to repurpose the plant as residential, retail, office, and light industry space as well as a recreation and art center over the next 10 to 15 years. Despite many years of neglect and abuse, the reinforced concrete structures remain mostly intact and structurally sound. Demolition and rehab work officially began in October 2014.

Russel Industrial Center

Covering 2.2 million square feet, this eight-unit complex began as a production facility for Anderson Carriage Company. Though originally a horse carriage maker, Anderson had produced the first auto bodies in 1901 for Hall of Fame Inductee Ransom E Olds. Anderson began producing electric vehicles at the complex in the early 1910’s. Initially sold as Anderson Electric auto’s, the company changed its name to Detroit Electric in 1920, and continued producing electric cars till 1938. Like the Packard and Highland Park Plants, many of complexes’ buildings were designed by Albert Kahn and utilized his trademark reinforced concrete architecture.

After J.W. Murray ceased auto body production in 1955, the complex was partially repurposed into a printing plant. Though there were various tenants, most of the sprawling complex remained dormant during the intervening decades and changed hands sporadically until the 2003, when it was purchased by Dennis Kefallinos. Today, the complex is mainly leased out as studios for artists, photographers, woodworkers, metal fabricators, painters, and musicians. It is also a trade center and a site for many Hollywood films and music videos. In 2014, Chevrolet revealed the C7 Corvette at the complex.

Albert Kahn; Architect of Production

This inductee never designed, engineered or built a car. He never ran a car company, operated an automotive supplier, or owned a dealership. His contribution to the automobile industry, however, can be measured, quite literally, in stories. Looking for a better solution to the standard wood-framed factories of the day, Kahn first utilized his novel reinforced concrete technique to construct a Packard Motor Car Company factory in 1905. The factory attracted the attention of Henry Ford, who hired Kahn to design the Ford Motor Company’s Highland Park plant in 1908. This would begin a long relationship between Kahn and Ford, and would be one of many relationships the architect would build with automakers in Detroit and around the world. He was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2012.

This inductee never designed, engineered or built a car. He never ran a car company, operated an automotive supplier, or owned a dealership. His contribution to the automobile industry, however, can be measured, quite literally, in stories. Looking for a better solution to the standard wood-framed factories of the day, Kahn first utilized his novel reinforced concrete technique to construct a Packard Motor Car Company factory in 1905. The factory attracted the attention of Henry Ford, who hired Kahn to design the Ford Motor Company’s Highland Park plant in 1908. This would begin a long relationship between Kahn and Ford, and would be one of many relationships the architect would build with automakers in Detroit and around the world. He was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2012.