As a visionary trailblazer in car design McKinley W. Thompson, Jr. brought creativity and foresight to some of America’s most iconic car models and was the first African American automobile designer at the Ford Motor Company. Born and raised in New York City, 12-year-old Thompson was inspired to design cars when he saw the sleek, futuristic profile of a silver Chrysler DeSoto Airflow. There was no role model for him in the field at a time when African Americans faced discrimination in education and the workforce. He took commercial art and drafting courses before taking a job as a draftsman in the National Youth Administration and later the Army Signal Corps. During World War II, he was drafted into the Army Corps of Engineers. After the war, Thompson worked for the Army Signal Corps—but he never stopped thinking about automotive design.

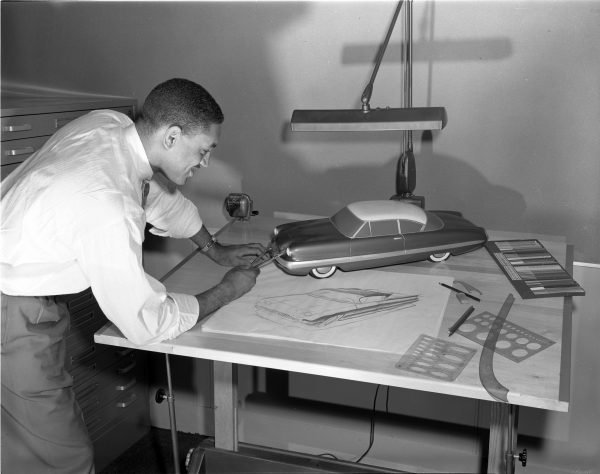

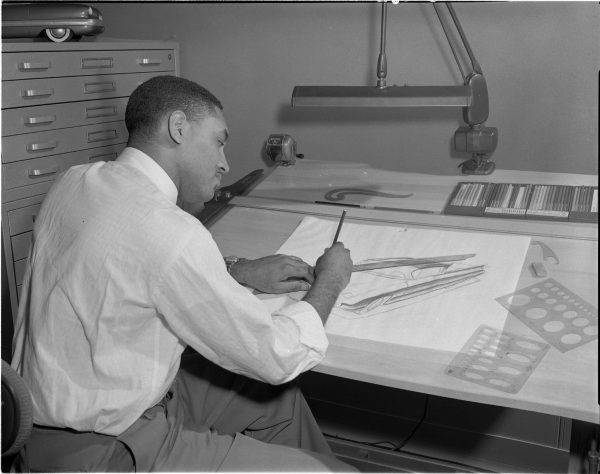

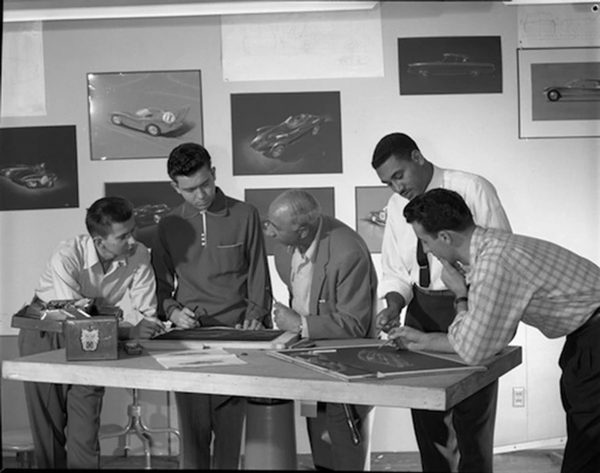

In 1953, Motor Trend magazine advertised an automotive design contest. The prize? A four-year scholarship to the prestigious Art Center School in Los Angeles, a leader in industrial design training. Thompson’s car design submissions featured unusual features, such as a gas turbine engine and reinforced Royalex plastic panels. His accompanying essay predicted future cars would focus on “more functional roominess and reduced size.” Thompson’s prediction was prescient, even as American car companies were building progressively larger massive steel automobiles. Thompson won the contest and became the first African American to matriculate at Los Angeles Art Center School. In 1956, he joined the Ford Motor Company’s Advanced Styling Studio and became Ford’s first African American designer. The studio produced concept car designs, such as the Gyron—a two-wheeled car. Thompson gained a reputation as a dependable designer, working on iconic models including the Mustang, Bronco, Cougar II, Thunderbird, and Falcon. At the time of his retirement in 1984, he led a team of fifty employees.

In the mid-1960s Thompson began work on the Warrior model—a rugged, lightweight, simple vehicle—designed for unpredictable roads and diverse terrains of developing nations. During 1960s decolonization movements around the globe, nascent governments sought tools for infrastructure development. Thompson envisioned the Warrior and its small factories as a way to locally build lightweight, durable products using Royalex plastics, including cars, boats, and “habitat modules.” In 1967, Ford stopped supporting the project for financial reasons, but Thompson obtained private funding and worked on the Warrior design privately until 1979. He refined the model and sought funding for production. While many expressed interest in the concept, Thompson never obtained reliable funding. He donated the prototype in 2001 to the Henry Ford Museum.

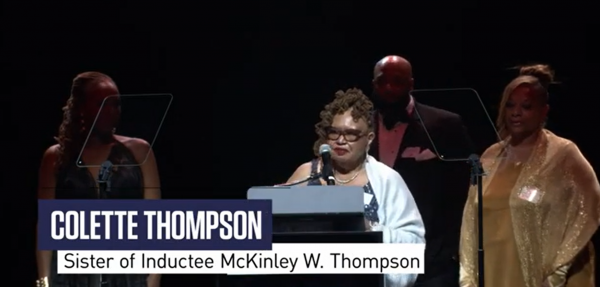

Thompson broke barriers as Ford’s first African American automobile designer, and his foresight in integrating plastics and reducing the size of cars was finally validated in the 1970s as cars began to downsize, and 1990s when plastic body panels became more common. His localized factories concept came to fruition with the URI company in Namibia. After retirement, Thompson designed and produced a traveling exhibit about African American automobile designers that he took to malls and museums to inspire children to pursue their dreams. As a designer, visionary, and community servant, Thompson contributed to expanding the boundaries of the automobile industry.